In the Footsteps of the Medici: Murder and Intrigue at the Heart of the Renaissance

|

From its worn cobbled streets to its imposing medieval skyline, Florence’s historical center is steeped in history. Since its foundation in the first century B.C., the UNESCO world heritage site has played center stage to innumerable murders, affairs, intrigues and conspiracies. Because of this, Florence’s historical fabric is as dense as it is complicated – blending roman, renaissance and recent. But if there’s a thread that can be woven throughout the city’s most famous period, the renaissance, that thread must be the family of the Medici.

Despite humble beginnings as merchants and bankers, the Medici enjoyed such a meteoric rise to power that, by the 15th century, they had become de facto rulers of Florence. Godfathers of the renaissance, during their preeminence between the 15th and 18th centuries, the Medici produced three popes, financed kings, patronized geniuses like Michelangelo, Donatello, and Botticelli, and exerted enormous financial and political influence across Europe.

This article tells the story of this remarkable family, played out against the dramatic backdrop of the medieval city of Florence. And if you like what you read, be sure to sign up for one of our Roman Candle Tours so you can experience the wonders of Florence for yourself. We start at the city’s most well known landmark: the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore – known more famously as the Duomo.

Piazza del Duomo and the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore

While the façade of Florence’s great cathedral has changed a lot over the last five hundred years, both the piazza and the throngs of people who populate it have not. Spend Easter Sunday in Florence today and you can easily imagine the jostling crowds of spectators, pushy street-sellers and foreign visitors congregating outside the Cathedral of Santa Maria Del Fiore on Easter Sunday 1478.

As High Mass approached, these crowds would have seen the ‘magnificent’ Lorenzo de’ Medici – current head of Florence’s most powerful family – processing into the church beside his handsome but hobbling brother, Giuliano, and his friends and companions, Francesco de’ Pazzi and Bernado Baroncelli.

Craning their necks to get a better view, some might have witnessed Francesco playfully putting his arm around Giuliano and giving him a squeeze – supposedly teasing him about his the limp from his recent injury but in reality checking he wasn’t wearing armor. But most wouldn’t have noticed, distracted instead by the colorful festivities taking place in the shadow of Brunelleschi’s recently completed dome.

What these crowds wouldn’t have witnessed were the events that followed behind the cathedral’s façade – among the bloodiest in the city’s history. As the Host was raised before the High Altar, Francesco and Baroncelli attacked Giuliano, stabbing him 19 times with such frenzy that Francesco at one point missed Giuliano and drove his knife straight through his own thigh.

At the same moment two clerics, Antonio Maffei and Stefano da Bagnone, drew their knives and charged Lorenzo, striking a glancing wound to his neck. Bleeding from his wound, Lorenzo fled, taking refuge behind the giant bronze doors of the sacristy while the conspirators exited the church. At least for now, he was safe.

The motives for the attack had been both political and personal. The Pazzi family ranked among the Medici’s greatest rivals. Their wealth and prestige were enormous: one ancestor was allegedly the first to scale the walls of Jerusalem during the First Crusade. But they had little political influence given the Medici’s monopoly on Florence’s government. The Pazzi conspiracy was intended to put Medici domination to an end, and open up access for Florentine families. But to accomplish this, the second part of the plot would have to succeed.

Piazza della Signoria and the Palazzo Vecchio

|

| Photo credit: Wikipedia |

Less than half a mile south of the mounting confusion around the Piazza del Duomo, other events were in motion. Ascending the grand staircase of the Palazzo Vecchio, Francesco Salviati, the Archbishop of Pisa, was hurrying to his meeting with the Gonfaloniere – the Florentine republic’s symbolic figurehead. But this wasn’t to be an ordinary meeting. Salviati intended to set his Perugian mercenaries upon the Gonfaloniere, killing him and seizing control of the palace. Unfortunately Salviati was a nervous man by nature, and before long his growing anxiety gave him away, leading to his arrest and that of his mercenaries.

Meanwhile in the Piazza della Signoria below, the head of the Pazzi family, Jacopo Pazzi, had taken up position in the along with 150 mercenaries of his own. Blissfully unaware of Salviati’s failure within the Palazzo Vecchio, he was anticipating the populace’s imminent revolt. But he’d fatally misjudged it. News of Lorenzo’s survival was slowly starting to trickle around the city, animating the pro-Medici population. Baying for the conspirators’ blood, they forced Jacopo to flee the city. Others were not so lucky.

Giuliano’s assassins, Francesco de’ Pazzi and Bernado Baroncelli, were arrested, stripped, and thrown from the window of the Palazzo Vecchio, left to hang in full view of the jeering mob in the piazza below. Next to join them was Archbishop Salviati. With his hands bound he was thrown from the window; writhing and struggling in vain to get purchase by biting into the naked corpse of Francesco de’ Pazzi swinging beside him.

Nor did the bloodshed stop there: over the following days 80 people were convicted of conspiracy against the Medici. The punishment meted out was the same – thrown from the Palazzo Vecchio with nooses around their neck, these men were left to sway and decay in full sight of the Florentine population.

The summary execution of these conspirators is a small footnote in the Piazza’s long and bloody history. In the late 14th century it was the setting of a pitched battle at the climax of the Ciompi Revolt. In 1497, the zealous cleric and enemy of the Medici, Girolami Savonarola, used the piazza for his Bonfire of the Vanities – an event that saw thousands of priceless artworks destroyed. The following year would see a dramatic reversal in fortunes for Savonarola though. Declared a heretic and excommunicated by the papacy he was hanged and burned in the center of the piazza – a commemorative plaque still marking the spot.

The period after Savonarola’s execution was a golden age for the Medici. From 1513 they had their own pope – Leo X, the second son of Lorenzo the Magnificent, and a man of magnificently unusual tastes himself. It was said that he found entertainment in watching naked boys leap out of giant cakes, giving all new meaning to the term kinder surprise. He also reputedly had a boy painted gold from head to toe and paraded through the streets during his triumphal procession into the city. Unsurprisingly, the boy died the next day. But this did nothing to bring the papal partying to an end, and the festivities continued for the next few days.

In 1530 the city became the Duchy of Florence after the French returned power to the Medici. For all intents and purposes, the city was now a Medici monarchy, and its first monarch was Cosimo I. In 1540 Cosimo – whose statue occupies the center of the piazza – had the Palazzo Vecchio revamped to become his family’s official seat of power. Soon after, he would relocate to the Palazzo Pitti across the river. But first, Cosimo needed administrative offices for his regime. So commissioning Giorgio Vasari, he set upon building arguably the world’s most beautiful and famous office building: the Uffizi.

The Vasari Corridor

Constructed under Cosimo I, the lenghty Vasari Corridor runs from the Palazzo Vecchio through the Uffizi, along the Ponte Vecchio and to the Palazzo Pitti. Cosimo claimed to have commissioned the corridor for his son’s wedding (god forbid his bride should ruin her dress by stepping through that street level filth!) But in reality, Cosimo had more devious reasons.

Practically invisible from street level, the Vasari Corridor allowed Cosimo to spy on the populace below, giving him the upper hand on any would-be enemies. And such enemies were everywhere; one failed assassin, Giuliano Buonaccorsi, met a particularly sticky end – publically branded with irons en route from the Bargello to his execution upon the scaffold of Piazza Signoria.

Mainly the Vasari Corridor offered Cosimo a safe and secretive commute from his residence to his workplace. But don’t think the great duke would have been content to commute on foot. Vasari designed it to be wide enough for Cosimo to ride his personal carriage through.

The Ponte Vecchio

Perhaps Florence’s most iconic landmark, the Ponte Vecchio has connected the north side of the city with southern Oltrarno – literally meaning ‘beyond the Arno’ – since antiquity. Previously in the hands of butchers, in 1593, Cosimo replaced them with gold merchants (presumably to make his commute more pleasing to the nose).

One of the lesser-known curiosities on the Ponte Vecchio is the Mannelli Tower. Follow the Vasari Corridor along the bridge and you’ll see that it awkwardly curves around a tower. The reason for this is that the Mannelli family refused to destroy their tower to make way for Cosimo’s corridor, meaning that Vasari had to build his corridor around it. One can only imagine how uncomfortable that must have been for glaring Mannellis and builders alike during the corridor’s construction.

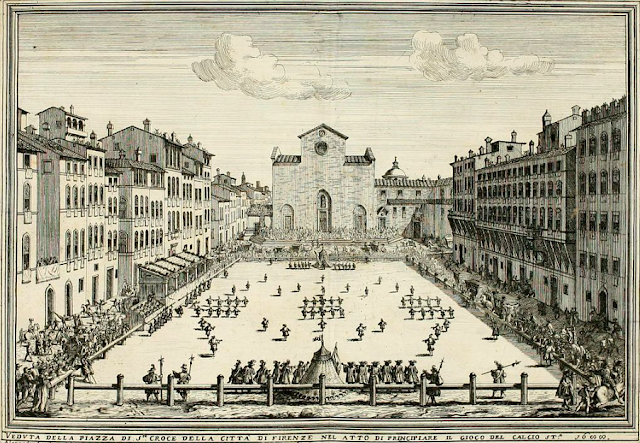

Piazza Santa Croce

Since the 16th century the piazza that stretches before the breathtaking Basilica of Santa Croce has played host to calcio storico. Believed to be the world’s most brutal sport and still played annually, calcio storico (or ‘medieval football’) resembles something like all out warfare, with sprinkles of boxing, rugby and football added for good measure.

Among it’s historical competitors were several Medici: Piero de’ Medici (Lorenzo the Magnificent’s son), Lorenzo II and Alessandro I de’ Medici. The latter was a particularly lurid character. Of a voracious sexual appetite, Alessandro was ultimately assassinated by his own cousin who lured him to his apartment for a night of passion with his sister. But that’s the last we’ll say about the later Medici, as for our last site we must go back to our first story: the Pazzi Conspiracy.

Basilica of Santa Croce

Many of the Pazzi family were summarily hunted down and killed in the aftermath of the conspiracy. We’ve briefly met one of these figures already –the hapless head of the family and our failed revolutionary, Jacopo de’ Pazzi. Jacopo briefly managed to escape the city but was soon captured and brought back, tried and executed.

His body was briefly interred in the Basilica of Santa Croce, the current resting place of such historical titans as Michelangelo, Machiavelli and Galileo. But, presumably seeking a definition for the term overkill, Medici supporters dug up his corpse, dragged it through the streets, decapitated it (briefly using his head as a doorknocker) and then threw it into the Arno – after which it was fished out, flogged again, and thrown back in.

Jacopo de’ Pazzi’s corpse didn’t have much longevity, but his family’s legacy did. Since 1443, Brunelleschi’s breathtaking Pazzi Chapel has stood within the grounds of the Basilica of Santa Croce. One of the more hidden wonders of renaissance architecture, the chapel served two purposes: enhancing the family’s prestige in the city and allowing them safety and security in their private worship.

The Medici line ended in the 18th century, not through political intrigue or assassination but because they failed to produce any legitimate heirs. But this wasn’t the end of their contribution to the city. The last Medici, Anna Maria Luisa, signed away all her family property, including the artworks, to the state of Tuscany on the proviso that nothing would ever be removed from the city.

Her rationale was to ensure that the Florentines benefitted from their city’s immeasurable artistic legacy and that the city continued to draw visitors from all over the world. Visit Florence today, and you’ll agree that on both accounts she succeeded.

Written by: Alex Meddings

If you liked this article, read also “SEVEN QUESTIONS ABOUT FLORENCE YOU WERE TOO EMBARRASSED TO ASK”

This comment has been removed by the author.