It was during these years that the Venetians got a spiritual leader who was as much a reflection of his city as he was of Catholic teaching. Albino Luciani, Patriarch of Venice from 1969 to 1978, was a modest and moderate man who championed the poor and eschewed the trappings of office for a simple and humble life more in line with Christian doctrine. At the same time, there was something of the fantasist about Luciani; an avid reader of fiction and writer of fictitious letters, he was in some ways suspended between the real world and the world of dreams and the imagination, much like Venice itself.

By the time Luciani was created a cardinal by Pope Paul VI in 1973, he had already started writing the collection of letters that would shed much light on the personality of a man destined to be catapulted to fleeting fame just a few years later. Released in 1976 under the title Illustrissimi (Most Illustrious), the volume gathered together 40 letters that had previously been published in the Messaggero di Sant’Antonio, a monthly Catholic review. While the letters invariably dealt with difficult moral issues, they did so with a humorous tone, simplicity, and lightness of touch that readers found highly appealing. In essence, Luciani had discovered an ingenious way to convey complex thoughts in everyday language so that leading Christian figures such as St. Theresa of Avila, St. Bonaventure, St. Bernard of Clairvaux, and indeed even Jesus Christ himself, felt approachable, accessible to the ordinary man and woman.

Luciani’s letters were addressed to a far more diverse group of recipients than just Catholic saints and theologians though. The cardinal’s love of literature shone through in epistles to Mark Twain, Petrarch, Carlo Goldoni, Walter Scott, and Charles Dickens. The beginning of his letter to Dickens is wonderfully direct:

“Dear Dickens, I am a bishop who has been given the odd task of writing a letter to an eminent person every month… I saw an advert in a newspaper for your famous Christmas books and thought to myself ‘I’ll write to him. I read his books as a boy and really loved them; they were filled with love for the poor and a sense of the need for social reform, they were warm and imaginative and human.’ So here I am bothering you.”

He goes on to “bother” Dickens by praising him for his love and concern for the poor, by outlining the advancements that trade unions have brought about for workers’ rights since the writer’s time, and by pondering on the future of the environment, social justice, and the developing world.

As a beloved character familiar to both Italians and (thanks to Walt Disney) to people all around the world, Pinocchio was arguably the most memorable of Luciani’s illustrious letter recipients. The Pinocchio letter encapsulated the sensibility of a man firmly rooted in the lives of the ordinary people. Luciani’s were not the abstract musings of an esoteric theologian, but rather the humble thoughts of a compassionate and simple man – a compassionate and simple man on the cusp of far greater glory. In Venice, it was said that the door of Luciani’s residence was always open to anyone who passed by, whether they be prostitutes, addicts, homeless people, or even priests – in the late 1970s, however, the cardinal would leave his residence.

In early August 1978, after a papacy lasting 15 years, Pope Paul VI died at his summer residence in Castel Gandolfo in the picturesque hills above Rome. With the college of cardinals deeply divided into two rival factions headed by the conservative Cardinal Siri of Genoa on the one side and the progressive Cardinal Benelli of Florence on the other, a consensus candidate for pope was needed who was acceptable to both factions. Pretty soon that consensus candidate would be Polish cardinal Karol Wojtyla; but Wojtyla’s time was not quite yet. First, there was another consensus candidate to be given a chance, and that man was Albino Luciani.

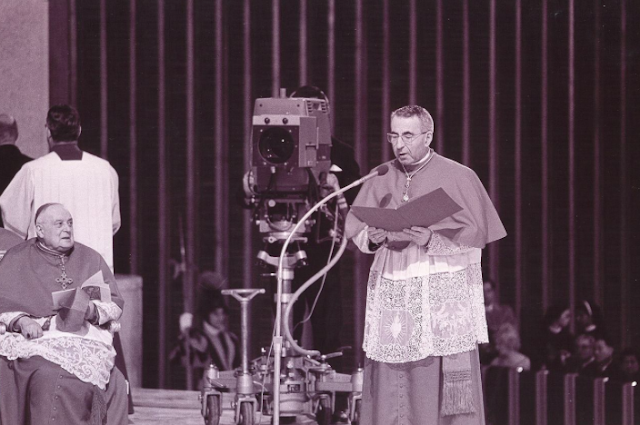

On August 26th, 1978, Luciani was duly elected pope on the fourth ballot of the conclave (papal election). Although apparently aware that he was a contender going into the conclave, Luciani was said to have had no wish to become pope, declaring to his fellow cardinals on election: “May God forgive you for what you have done.” Upon election, Luciani selected the double name of John Paul, a complete innovation at the time and a clear sign of what type of papacy he had in mind – by evoking his two predecessors, John XXIII and Paul VI, he was indicating a desire to continue with the reforming spirit of the Second Vatican Council over which they had presided. In the celebratory mass to greet his election in St. Peter’s Basilica, the new Pope John Paul I had no official coronation, as he refused to wear the papal tiara or be carried about in the sedia gestatoria (portable throne). This hugely symbolic rejection of papal pomp would be echoed 35 years later with the election of Pope Francis.

John Paul I’s time in the Vatican was extremely brief – in one of the shortest papacies in history, he died after only 33 days. What people most remember about him was his kind, smiling face; he is still affectionately referred to as “The Smiling Pope”. Questions still remain, however, as to why his peers elected someone who had a chronic heart-related medical condition. Some commentators have suggested that the cardinals deliberately elected Luciani because he was considered a simpleton who could easily be manipulated, a theory given ample airing in John Cornwell’s compelling account of the death of John Paul I, A thief in the night. But not everyone agrees with this interpretation, particularly given the steel displayed by Luciani as a cardinal in exposing financial corruption. Indeed, his intention to look into the shady dealings of the IOR (Vatican Bank) upon his election has led many people to wonder whether Pope John Paul I might have been murdered. While unsubstantiated conspiracy theories abound, what is beyond doubt is that the Vatican press department made a real mess of dealing with the pope’s decease, releasing information that was inconsistent and, on certain points, downright contradictory – e.g., regarding the time of death and sequence of events, in one reconstruction the prescient undertakers arrived before the pope had even died! The Vatican’s incompetence in the matter ensured that anyone with a vivid imagination could come up with the most shocking theories – John Paul I’s death was even used as inspiration for the plot of The Godfather Part III.

Luciani’s own vivid imagination did not desert him either during his brief tenure as pope. Delivering the Angelus one Sunday from the window of his residence overlooking St. Peter’s Square, he declared:

“God is a FATHER, and even more so a MOTHER.”

The remark caused consternation among flustered Catholic theologians, who, having spent two millennia trying to formulate and explain the difficult concept of the Holy Trinity (the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit), now had an added female presence with which to contend. While the words may have stumped the theologians, they were typical of Luciani’s inclusive and homely style and, ultimately, commemorated favourably on a Vatican stamp in 2012 celebrating the centenary of his birth.

Nowadays, visitors to the Vatican can happily visit the tomb of Pope John Paul I in the grottoes underneath St. Peter’s Basilica. The tomb is close to that of Luciani’s immediate predecessor, Pope Paul VI; his successor, Karol Wojtyla (aka St. John Paul II), the third pope in 1978’s “Year of Three Popes”, was moved up from the grottoes directly into a prime position in St. Peter’s Basilica a few years ago. And perhaps if Albino Luciani one day becomes a saint, he too might get bumped upstairs.

In the meantime, although he wasn’t around for long, Albino Luciani at least still has the distinction of being one of the most interesting and appealing popes of the 20th century. He can also lay claim to being the original John Paul, the one before the much more famous John Paul II. In the immortal words of British post-punk musicians, The Fall:

“Hey Luciani, you were the first John Paul one!”

If you liked this article, read also “WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT THE EXTRAORDINARY HOLY JUBILEE YEAR“