Exploring The Hidden Giants Of Ancient Rome

It’s no wonder Rome’s called the Eternal City. A rich architectural legacy, spanning over two millennia, bridges today’s metropolis with the city of the Caesars and the Rome of the popes. In Rome’s centre, you can barely turn a corner without stumbling upon something special—an arch, a column, or even an ancient temple. So much has survived from Rome’s heyday that we think we know the ancient city pretty well.

The Roman Forum was the ancient city’s hub, a melting pot of international trade, social ostentation, and political conspiracy. The Colosseum(or the Flavian Amphitheatre as it was then known) was Rome’s main arena: a sporting arena-cum-bloodbath where the imperial elite put on shows to placate the city’s plebeian masses—part of their diet of “bread and circuses,” as Pliny the Younger once wrote.

But when the Roman Empire fell, the city of the Caesars fell with it—its pagan monuments mainly destroyed, converted into churches, or, more often than not, simply built over. We’ve uncovered but a fraction of the ancient city that underlies the modern metropolis. And while some monuments, like the Pantheon, have survived haphazardly (in the Pantheon’s case only because of its last-minute conversion into a church), many of Rome’s ancient giants lie hidden. Hidden, but not forgotten.

Rome’s hidden giants still play their part in determining the city’s landscape. Some structures disappear or blend into modern buildings; others dictate the shape of what stands above. All have one thing in common though. That if you know where to look, they spill much more of Rome’s history than you could ever imagine.

In this post, Roman Candle Toursguide you through some of ancient Rome’s hidden giants. We’ll look at monuments that rival the Colosseum in scale and curiosities on a par with the Pantheon in their ingenuity. And we start in a place better known for its Christian rather than pagan past: the Vatican.

The Vatican: Caligula’s Circus and Obelisk

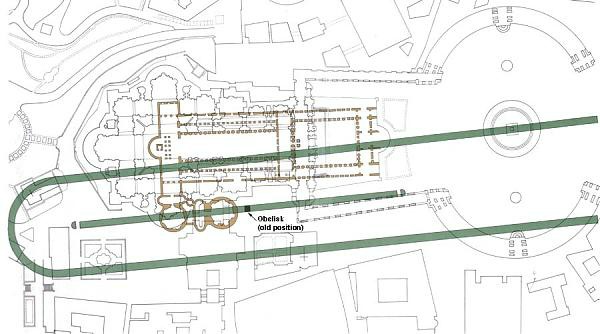

Artist’s imagination of Caligula’s Circus and an old Saint Peter’s Basilica. Photo credit: Roger Pearse

Visitors to the Vatican are rightly awestruck by its architecture: St. Peter’s Basilica, Michelangelo’s dome, and Bernini’s square. It’s no surprise that these imposing medieval structures dominate attention. This is after all the beating heart of Christianity. But the square’s more keen-eyed visitors might also ask themselves what a thirteenth century BC Egyptian obelisk is doing in its centre. It’s a good question. And like most questions about the Eternal City, it comes with a colourful answer.

The Vatican Obelisk was brought to Rome in 37 AD by the mad, bad, and dangerous-to-know emperor Caligula, who had a ship built especially for the task. Caligula initially installed it nearby in his private gardens before erecting it on the spina (central barrier) of his circus (completed by Nero), which now partly underlies the western wing of Saint Peter’s Basilica.

Photo credit: Roger Pearse

Here the obelisk remained until 1585, when Pope Sixtus V set about the thirteen-month project of reassembling it and moving it to its present location. Because this red granite obelisk weighs 330 tonnes, this was no easy task, and Sixtus entrusted it to the expert hands of famed architect Domenico Fontana.

To move the obelisk, Fontana acquired 40,000 pounds of hemp rope, 72 horses, and 900 men. But even this nearly proved insufficient. At one point while it was being winched up, the hemp ropes started to fray. The gathered crowd, threatened by pain of death should anyone utter a sound, stood shocked, silent, until an experienced Genovese sailor cried out, “water on the ropes!”

Photo credit: Framepool Footage

Photo credit: Framepool FootageFontana duly obliged, and by applying water to the ropes managed to finish winching the obelisk up, saving the monument from obliteration. As for the sailor, rather than being put to death he was rewarded for his intervention. Sixtus declared that from henceforth the Vatican would buy all its Palm Sunday fronds from the sailor’s hometown of Bordighera. It’s a promise the papacy keeps to this day.

Piazza Navona: Stadium of Domitian

Wander upon Piazza Navona and you’ll immediately be struck by the strangeness of its shape (not least because, unlike most piazzas, it isn’t square). The long, sculptured piazza instead takes a U-shape. For it stands precisely above the first century AD chariot-racing track of the emperor Domitian.

Domitian built his stadium—the first in Rome based on the Greek model—in around 86 AD on land cleared by a devastating fire six years earlier. It was used mainly for athletic performances, but also saw gladiatorial contests, Christian executions, and, from its arcades which doubled up as brothels, some of the baser everyday acts of ancient life.

The present piazza gives a good sense of its dimensions. At 275 metres long, 106 metres wide and 30 metres high, Domitian’s stadium could accommodate 30,000 people.

The stadium gradually fell out of use until Late Antiquity, when its arcade was used to shelter the poor. Its rubble was then robbed piecemeal over the centuries, recycled and incorporated into other building projects. Parts of the stadium are, however, pretty well preserved. You can still see its travertine arches beneath the I.N.A. Palace at the far end. The rest can be viewed through by visiting the Stadium of Domitian.

Palazzo Massimi alle Colonne: Odeon of Domitian

Photo credit: Rome Art Lover

When the emperor Constantius II, Constantine the Great’s son, visited Rome in 357 AD, he was awestruck by one of the ancient city’s most widely recognised wonders: the Odeon of Domitian. In terms of its beauty, it was, according to the fourth century AD writer Ammianus Marcellinus and the event’s narrator, on a par with the Pantheon, Domitian’s Stadium, and, next on our list, the Theatre of Pompey.

Photo credit: Rome Art Lover

The Odeon has now disappeared completely from sight: a victim of the Eternal City’s historical ebbs and flows which have resulted in the haphazard preservation of Rome’s architectural legacy. But walk along the modern Corso Vittorio Emanuele and you’ll come across the curved façade of Palazzo Massimi alle Colonne. This palace’s curve was not a conscious architectural choice, but took its shape from the building that belies it.

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

It is specifically the Odeon’s stands the give shape to palace’s façade, designed to accommodate around 10,000 spectators who would flock to the Odeon for musical and theatrical performances. As befit its function, the Odeon resembled as an extraordinarily beautiful ancient Greek theatre. As befit the man who built it, its construction was an expensive, populist gesture, which went down brilliantly with the people and sourly with Domitian’s rival aristocrats.

Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

Other than the Odeon’s outline, preserved in the curvature of the palace’s façade, the only thing left of Domitian’s remarkable structure is a single cipollino column. It’s seen better days, and being situated in the centre of an inner-city car park you can’t help fear for its longevity, especially given the devil-may-care nature of Roman driving. But for now it stands: a neglected vestige of one of Rome’s most remarkable monuments.

Largo di Torre Argentina: Theatre of Pompey

Photo credit: Pin the Map Project

Sheltered from the traffic of one of inner city Rome’s busiest crossroads, the archaeological area around the Largo di Torre is one of the most curious ancient sites in the city centre. Its ruins are poorly signposted—so much so, in fact, that most people survey them to spot the cat sanctuary rather than the site where Julius Caesar was assassinated.

On the Ides of March 44 BC, the great dictator met his bloody end in the newly built Senate house annexed to the theatre of his great rival Pompey Magnus. Here, beneath a statue of Pompey, he was stabbed 23 times in one of history’s most famous (and most botched) assassinations, ushering in the end of the more democratic Roman Republic and the beginning of the monarchical Roman Empire.

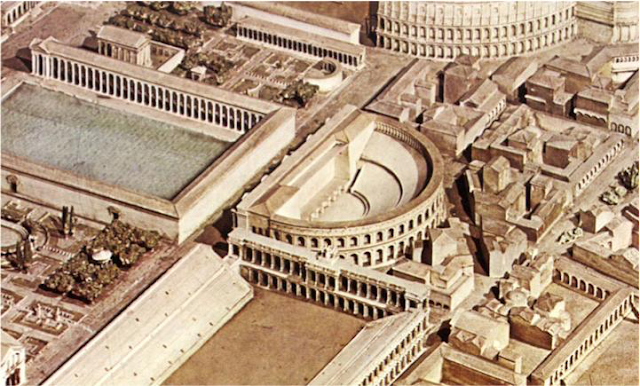

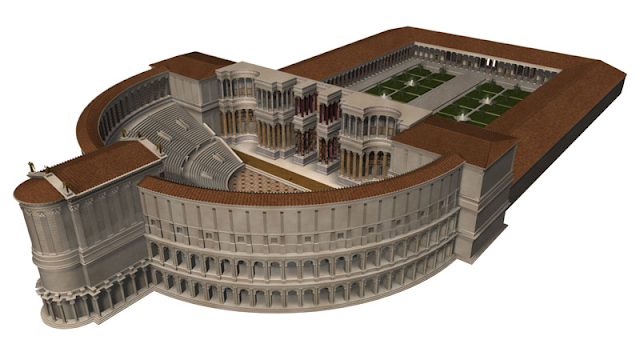

Reconstruction of Pompey’s Theatre. Photo credit: King’s College London

Though archaeologists believe they have identified the spot where Caesar was killed, nothing remains of his rival’s 17,500 capacity theatre annexed onto the site. This is all the more surprising given its historical significance. For, as the first permanent stone theatre in Rome, the Theatre of Pompey was one of the defining monuments of the late Republic.

Funded from the proceeds of Pompey’s many wars, the theatre was incredibly symbolic: a populist political gesture aimed at getting the people onside by building for them a state-of-the-art public venue.

Building stone entertainment arenas in the city was, in fact, politically prohibited, partly because the Romans feared such populist gestures and partly out of a general disdain for ‘too much’ of the arts. Pompey was only able to get round this prohibition because he could claim it was a stairway leading to the Temple of Venus “Victory” at the top (which, technically speaking, it was).

Piazza di Grotta Pinta perfectly preserves the curve of the theatre’s cavea. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

The Theatre of Pompey may be invisible on the surface, but in terms of Rome’s topography it’s one of the best examples of urban continuity in the city. Completed in 55 BC, it was restored numerous times over the centuries after fires and other natural disasters before being built over entirely. But the shape and site of its large curve are perfectly evident from the bend in the buildings above it on the Piazza di Grotta Pinta.

Ludus Magnus: The Colosseum

Photo credit: Spotting History

All year round, people gather outside the Colosseum to marvel, line up and get photos in front of the most famous monument in Italy. When in Rome, a private Colosseum tour is a must, especially if you want to unlock the secrets of this remarkable amphitheatre. But you should also make the time to visit its surrounding neighbours, each of which offers its own unique insight into Rome’s incredible past.

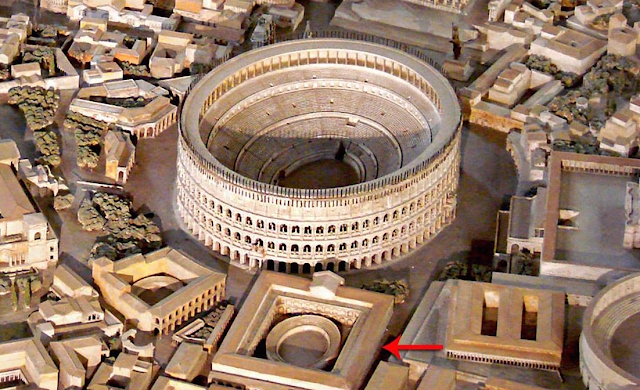

Just a few minutes walk east of the Colosseum, concealed beneath the modern street level of the Via Labicana and the Via di San Giovanni in Laterano, is the Ludus Magnus: the largest of four gladiatorial training schools built in the area around the Colosseum.

On the left is the gladiators’ living quarters; on the right what remains of their training amphitheatre

Built by the emperor Domitian (81 – 96 AD), whose family, the Flavians, constructed the Colosseum, the Ludus Magnus was a multipurpose facility serving as the residence and training centre of the Colosseum’s gladiators. It housed staff too: trainers, administrators, cooks, surgeons and (where surgery failed) morticians.

Photo credit: Capitolvium

Only one of its original three stories of accommodation cells survives, though even this is enough to give you a sense of scale for the living quarters alone (each cell housed up to five men). More eye-catching, however, is the section of small amphitheatre where the gladiators used to train and vague traces of its cavea(seating area), spacious enough for 3,000.

The remainder of the amphitheatre and the Ludus Magnus at large is lost, irrecoverably built over by the modern road. Were it not for archaeological efforts in the twentieth century, we would be none the wiser that the Ludus Magnus was once directly connected to the Colosseum via a long (and regrettably no longer accessible) tunnel.

Meta Sudans (The Sweating Cone): The Colosseum

The concrete foundations of the Meta Sudans

The last of our monuments takes us just outside the Colosseum to the junction between the Arch of Constantine and the beginning of the Via Sacra and the Roman Forum. All you can see now are its concrete foundations, cut into a grassy mound that doesn’t draw so much as a second glance from the Colosseum’s visitors.

But in its day, from its construction during the reign of Titus (79 – 81 AD), it was a 20 metre high conical fountain, with a width of 16 metres, standing in a pool 1.4 metres deep, and designed so it seemed to sweat water (hence its name, Meta Sudans, which means “sweating meta” in Latin).

Traditionally, a metawas the conical structure that stood at either end of chariot-racing tracks and marked the point the charioteers had to steer around. The Meta Sudans served a similarly pivotal purpose. Only it featured at an event that carried far more prestige at a significantly slower speed.

Artist’s imagination of the Meta Sudans in its imperial heyday. Photo credit: Detritus of Empire

Standing in the back of a chariot, dressed up as Jupiter, with a slave behind him whispering a reminder in his ear that he was only mortal, a victorious general would pivot around the Meta Sudans during his triumphal procession over a vanquished enemy.

He would have come from the Via Triumphalis, its streets lined with adulating crowds hoping to be showered with spoils and plunder from his victorious campaign. From the Meta Sudans, he would make his way up the Via Sacra into the Roman Forum and toward the climax of his triumphal parade at the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus.

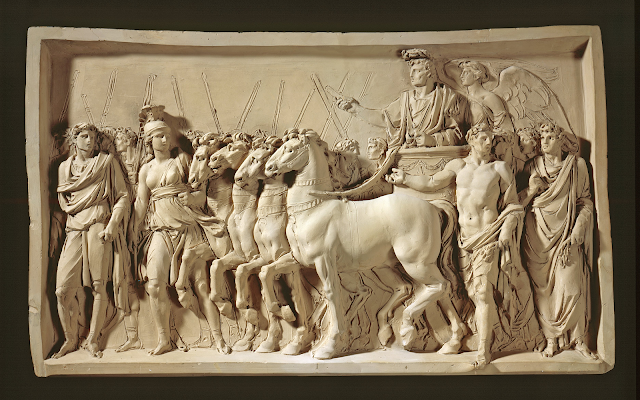

Relief of Titus’s triumph from the Arch of Titus in the Roman Forum. Photo credit: Ancient History Encylopedia

The Meta Sudans stood in a state of disrepair from antiquity to the modern age. By the twentieth century, and the dictatorship of Benito Mussolini, only its brick core survived brick core survived. Then, in 1936, the dictator had it hurriedly razed to create space for Fascist parades around the Via dei Fori Imperiali. It was only in the 1980s that its overlooked concrete foundations were excavated.

Roman Candle Tours in Rome

Roman Candle Tours offers a wide range of guided, private tours of Rome, many of which either incorporate or take you past these remarkable sites. Whether you’re interested in classical, medieval, or Baroque Rome, we’ve designed our tours to bring you the best of the Eternal City. But if something here’s caught your eye and you’d like to organise your own itinerary, get in touch and we’d be happy to talk you through one of our tailored tours.

Great post! The laudable destinations of Italy summarized in a single blog. It can entice people to apply for Italy Visa UK & head to this amazing tourist destination. Thank you for sharing the images. Keep up the good work